At the Ara e Madhe refugee camp in Shkoder (also called Scutari) in northern Albania, I was met by Doctor Maria Grazia Saramel taking a young Kosovar woman to the refugee hospital. Before arriving in Albania, I had heard that health care for the refugees was a major concern. As we approached the refugee hospital, Dr. Saramel warned me to prepare myself for what I was about to see.

On entering the dark corridors of the main refugee hospital I was struck by the strong smell of urine. Dirty floors and walls continued throughout the building. Stray cats and other animals wandered inside.

Aid workers in the camp were reporting that seriously ill patients might be better off staying away from the hospitals. The doctor on duty, working under Dr. Muhamet Bushati, provided me with a long list of the equipment that was lacking: sonograms, X-ray machines, hypertension kits. The list went on. Medical drugs were also in short supply; but surprisingly, when I asked if they had birth control supplies, the doctor said they had “everything” they needed, and were performing sterilizations and pregnancy terminations (abortions).

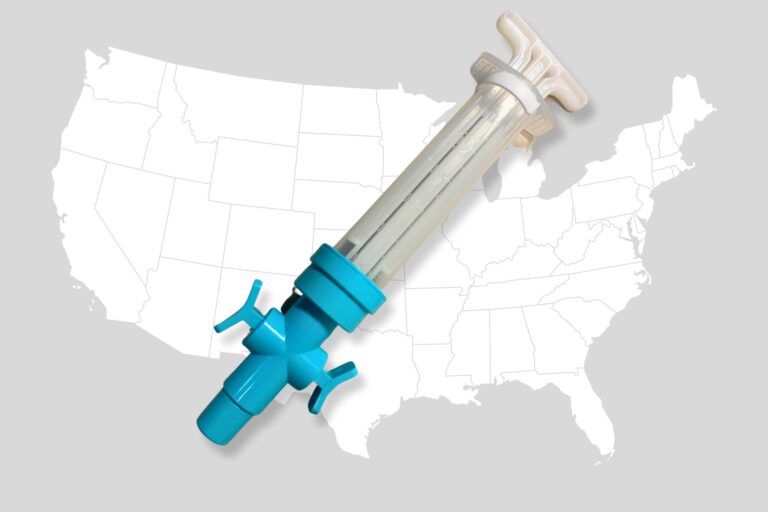

UNFPA Launches Campaign

On 8 April 1999, the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) announced that it was sending “Emergency Reproductive Health Kits” to Albania, sufficient for about 350,000 people. I found that these kits include subkits with condoms, birth control pills, “emergency contraception” or “morning after” pills, intrauterine devices (IUDs) and manual vacuum aspirators (MVAs — uterine evacuation devices used for early term abortions) as part of the “complications of abortion kit.”

The UN originally labeled these subkits “Pregnancy Termination” kits, but that name was changed to “reduce the risk of offending sensitivities and possibly make the subkit more acceptable.”1 But an abortion kit by any other name is still an abortion kit. While so much energy has been spent inventing euphemisms to market these supplies, the UN only belatedly realized the harm to women's health caused by untrained members of Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) distributing these pills and devices for birth control and abortion in the very dangerous and chaotic conditions that characterize refugee camps. “Both national and international staff vary in terms of their knowledge and experience in the area of reproductive health. Many of them are not even conversant with the issue or with specific interventions that need to be undertaken.”2 The UNFPA, after distributing these supplies to NGOs working in the refugee camps, is only now considering the provision of guidelines for proper usage of these dangerous drugs and instruments for “emergency contraception, pregnancy terminations, and optional method[s].”3

Kits Cause Complaints

Complaints began to emanate from Albanian refugee camps that UNFPA shipments of “reproductive health kits” at the Kukes border crossing from Kosovo, where most refugees have entered Albania, have been given priority over shipments of urgently needed health supplies, Dr. Gezim Bashka, head of maternity services in the Kukes hospital, reported to the Italian Press Agency AN SA on 22 April that they were short of antibiotics, sheets and serum but other materials had been arriving instead. “I do not want to seem ungrateful,” Dr. Bashka said, “but until now much superfluous material has arrived. Today a shipment of birth control. Explain to them that we need other things.” Even so, a consultant for UNFPA's Mission on Reproductive Health, Dr. Manuel Carballo, advised sending at least six months worth of reproductive health supplies to Skopje, Macedonia on World Food Program flights from Rome.4 This misguided emphasis threatens scarce room on the planes for badly needed food and basic health supplies to the refugees.

Pattern of Abuse

In Scutari, I discovered a pattern of abuse reaching back to at least 1995. Shortly after the fall of the Communist government, Dr. Enza Ferrara, who works at the hospital in Scutari, began to notice large shipments of IUDs arriving. She saw that women were being surgically sterilized without their knowledge or consent after delivering by C-section in the hospital. Time and again it fell upon her to inform women coming to consult her that a tubal ligation was the cause of their infection or inability to have children. She told me that her protests received a candid response from an Albanian Ministry of Health official: “we have accepted international aid on condition of reducing births.” Note that Albania has a very small population of three and a half million and a fertility rate in l997 estimated at an average of only 2.4 children per completed family.”5

'They Can't Have Children'

When the Kosovo refugees began streaming over the Albanian border, Dr. Ferrara began to provide health care in Scutari for the refugee camps. She told me that a visiting UN official approached her in the camps, to instruct her and others about the urgent need to provide “reproductive health” to the refugees, Dr. Ferrara asked the official what she meant by this, and why are such “needs” so urgent? The reply startled her. “The refugees are too many,” the U.N. official said. “We have to stop them from reproducing.”

“What about husbands and wives?” she asked.

“Don't you see they are refugees,” the UN official said. “They can't have children!”

Dr. Ferrara investigated the basis for this new instruction. In a manual entitled “Community Services for Urban Refugees,” issued by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees' (UNHCR) in 1994, she found, contrary to the official's directives, a clear statement confirming that refugees have the right “to procreate.” The directive from the UN official in the field gave population control precedence over health care and the human rights of refugees. (For more background on these directives, see “Heaping Injury,” in this issue.)

Planned Parenthood

Returning to Tirana, I visited the central offices of the Albanian Family Planning Association (AFPA), an affiliate of the International Planned Parenthood Federation (IPPF). The AFPA provided me with a report of its activity in the refugee camps, which I was able to verify. AFPA has mobilized all of its resources to gain access to the refugees. The AF PA also received large foreign donations (US $60,000 from IPPF and US$50,000 from the Planned Parenthood Federation of America (PPFA) for “reproductive health care kits and counseling), for population control among the refugees. I was also told by an AFPA official that PPFA stands ready to send in trainers with manual vacuum aspiration (MVA), and more “safe abortion” kits to supplement the already large quantities provided by UNFPA. The MVA devices are used to “evacuate the contents of the uterus” of a mother early in pregnancy. No concerns were expressed for the potential health risks to women who would have these unsafe abortions.6 A lack of facilities and adequately trained medical personnel at the refugee camps and in the refugee hospitals increases the likelihood of life-threatening complications such as hemorrhages or perforation of the uterus. The unsterile conditions increase the risk of sepsis infections, STD transmission, or contraction of pelvic inflammatory disease.

Trauma Precludes Consent

The AFPA official was, however, concerned that women are simply not coming to them for “reproductive health” services. He attributed this to the refugee women being “psychologically immobilized” by the trauma of the past few weeks. So the AFPA has started to “transport” refugee women, notably in the Vlora area, to the centers that provide these “services”.7 The AFPA official was unconcerned about the fact that trauma precluded informed consent; or that the transport van could be used to move refugee women who simply do not want to be transported to the birth control centers.

At a camp just outside Tirana (known as the “swimming pool camp” because it is built around the Tirana municipal swimming pools), health care for over five thousand refugees was being administered from two small tents. The doctors there told me that the “family planning people” had already come to the camp with their information, directing refugee women into the city for “reproductive health services.” These “family planners” provided no medicine for chronic conditions like diabetes and respiratory infections. I interviewed several women in this camp. Through a female interpreter, I was told that none of them knew what “birth control” or “family planning” meant.

Some of these same traumatized women were being transported to Albanian Family Planning Association centers or government maternity hospitals to receive “reproductive health” services. These centers are equipped with IUDs8, and sterilization and abortion equipment. The doctor in the Shushice refugee camp, near Elbasan, told me candidly that “no one had asked for contraceptives.” The refugees “have bigger problems on their minds,” he said. This fact was confirmed again and again in each camp I visited, in Scutari, Tirana, Durres, and Elbasan.

Fabricating Demand

The UNFPA has worked officially in Albania since 1991, with an office in Tirana since 1996. According to Dr. Daniel Pierotti, UNFPA Senior Advisor for Emergency Relief Operations, the UNFPA plans to bring “reproductive health” to all the camps of Kosovar refugees. Providing me with an English translation of the 1995 Albanian abortion law, he “assured” me that there was no problem with doing abortions in Albania through the 22nd week of pregnancy.

Dr. Pierotti confirmed that Albanian NGOs are being used to implement the recommendations of UNFPA consultant, Dr. Manuel Carballo, concerning the need to create demand for their products. Dr. Pierotti predicted there would be “demands” for abortion in a month or two and that these needs would have to be filled. Little or no demand for abortion exists among the refugee women. Dr. Carballo's recommendations include the statement: “Because contraceptive use is low in the populations in question, it will be necessary to consider some form of social marketing or promotion of methods.”9

Pushing Abortifacient Pills

Dr. Pierotti said that all the “Emergency Reproductive Health Kits” had been distributed, and that more would arrive by early May. Pierotti gave me a copy of a document dared 4 May 1999, which he co-authored, listing the recipients of the kits. The Albanian Ministry of Health had taken some so far, and the rest went to NGOs such as “[AFPA], the International Rescue Committee, Medicos del Mundo, Marie Stopes International…” to give to the refugees10 .

Dr. Pierotti said that “none of the raped women we see have come in within 72 hours of the fact,” the effective time limit for the “emergency contraceptive” doses, and therefore “it is really useless for now until later in the camps.” Dr, Pierotti expressed trepidation that it would become public knowledge the pills touted as a “post-rape kit” have proven useless for that purpose, but made no apologies for widely distributing the pills and other kits without guidelines, UNFPA spokeswoman, Corrie Shanahan, confirmed that UNFPA workers would encourage the use of “morning after” pills as a routine method of birth control.

Visibly upset, Dr. Pierotti burst out in anger over Congressman Chris Smith's (R- NJ) recent fact-finding mission in Macedonia, and Smith's questions about the use of emergency contraception. “He seems to have nothing else on his mind,” Pierotti said. “It is legal here, leave us alone.”

Despite it being legal, Pierotti addressed none of the human rights concerns surrounding the distribution of “morning after” pills as a standard form of birth control to refugees who had not been raped.

Danger Ahead!

The manufacturer of “morning after pills,” Schering Health Care, has recognized the lack of medical testing on the side-effects of multiple usage of these pills.11 NGOs distributing these pills have no way to monitor the misuse of these drugs.

The “reproductive health kits” were sent to Albania for distribution by NGOs to the refugees before other urgently needed medical supplies could reach refugee camps, and in advance of guidelines that could limit the danger to women from use of the abortifacient pills and MVAs. This raises serious concerns of violations of human rights, informed consent, women's health and elementary justice.

All of the dozens of refugee women I interviewed were “unaware” that they have needs for “reproductive health” services. But given the refugee crisis, the UNFPA and AF PA can press their foreign and ideological concepts of “reproductive health” onto this “captive audience.” Without demand for their “services,” the UNFPA has constructed a “social marketing” campaign to fabricate demand.

The refugee women are entirely dependent on the refugee camps for food, shelter, health care and protection . Unless the international community reacts immediately, methods already in place to rob the Kosovar refugees of their future children and their posterity will be carried out, adding yet another tragedy to the forced expulsion from their homeland.

Joseph Meaney is the Vice Director for Human Life International in Rome

1 United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). Proceedings for the Second Preparatory Meeting on Reproductive Health in Refugee Situations. Geneva: April, 5-6, 1995, 8.

2 Dr. Manuel Carballo, “Advanced copy of the Executive Summary and Recommendations of the Mission on Reproductive Health Need Assessment” (6-l3th April 1999), 5.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid., 4.

5 Families must have an average of at least 2.l children just to prevent natural population decline over time in a first world country with excellent health care and low infant mortality. An average of 2.4 children in a country of Albania's level of poverty may he enough to prevent population decline but will not produce much population growth.

6 Benson. J. et al. “Complications of unsafe abortions in Sub-Sahara Africa, a review,” Health Planning and Policy, 1996. 11 (2): 117-131. The authors found that there is insufficient information about the safety of these procedures at primary and secondary referral levels in developing countries.

7 AFPA, “Information on the activity of the Albanian Family Planning Association in support of the Kosova refugees,” 5.

8 The Multiload CU 375 IUD distributed by the UNFPA is labeled in English on the package “to be removed five years after insertion.” Given the unstable conditions of the camps, there is small likelihood that the refugee women will receive adequate attention in the case of bleeding or infection that may occur over this time span. Moreover, there is no way to determine when an IUD should be removed other than an accurate record of a woman's medical history, something again highly unlikely to come into existence in, much less survive, a refugee setting. There are serious health threats if this IUD is left in after the prescribed duration, including scarring of the uterus, ectopic pregnancy, and fetal infection which would he fatal to a baby which does survive to implantation.

9 Dr. Manuel Carballo, “Advanced copy of the Executive Summary and Recommendations of the Mission on Reproductive Health Need Assessment,” (6-13th April 1999), 5.

10 Drs. Manuella Bello and Daniel Pierotti, Update Information on UNFPA's role in Reproductive Health for the Kosovo Refugees,” May 4, 1999.

11 The Pharmaceutical Journal, 1995; 255: 143.