Due to a strong, culturally-rooted preference for sons in many parts of the world, millions of girls have been selectively aborted merely because their parents had wanted a boy instead.

In some patriarchal cultures, strong son preference leads to the practice of sex selection—methods some parents use to select the sex of their child, including sex-selective abortion, female infanticide, or post-birth neglect or abandonment.

In decades past, the practice of sex selection primarily involved neglect of daughters and female infanticide. Since the introduction of ultrasound technology made it easy and affordable for parents to find out the sex of their child prior to birth, the practice of sex-selective abortion became widespread in many parts of eastern and southern Asia, the Caucasus, and the Balkans. Most of these selective terminations have occurred in either China or India.

In India, we have found that approximately 15.8 million girls have gone ‘missing’ at birth due to sex-selective abortion since 1990. Due to varying assumptions on what the expected sex ratio at birth should be in the absence of sex selection, however, the actual number of sex-selective abortions in India could range from as low as 11.1 million to as high as 20.2 million.

SOME FACTS ABOUT INDIA’S SEX- SELECTIVE ABORTION CRISIS BY THE NUMBERS:

15,800,000

550,000

111

4%

WHAT IS SEX-SELECTIVE ABORTION?

Sex-selective abortion is the abortion of a preborn child simply because the child’s sex was not what the parents wanted.

In countries where culturally-rooted son preference is common, sex-selective abortion is used as a means to attain a couple’s desired number of sons and desired family composition. Sex-selective abortion constitutes violence against women and is a serious violation of the fundamental rights and equal dignity of women.

WHAT IS SEX SELECTION?

WHAT ARE SEX RATIOS?

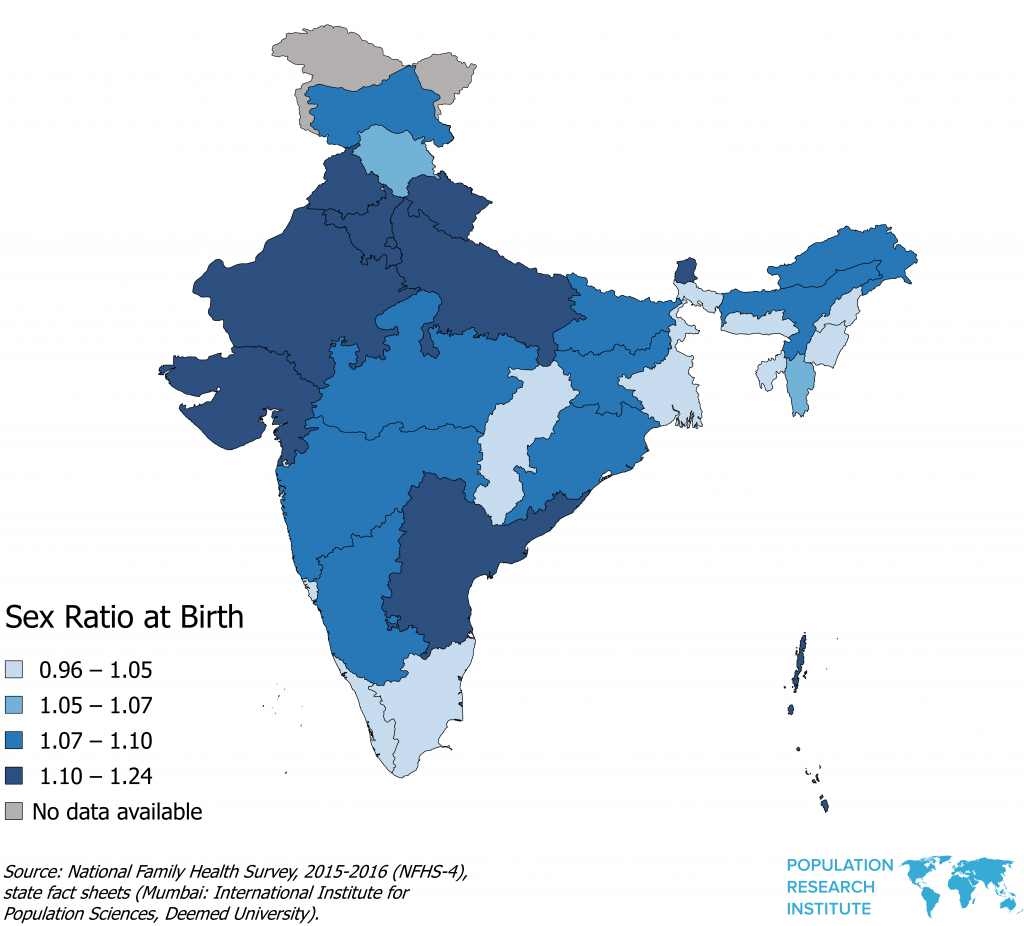

Sex Ratio at Birth by State in India

Click to View the Causes of Sex-Selective Abortion in India

1. Son Preference – Throughout much of India, sons are often valued to carry on the family name and receive inheritance. According to traditional Hindu custom, important religious rituals such as the lighting the funeral pyre must be performed by a son to assure that parents have a good afterlife. Sons also provide parents with the assurance that they will be cared for—physically, emotionally, and financially—in sickness and old age.

Daughters, on the other hand, are often seen as a burden and a net financial loss. Although illegal, the practice of dowry is still common in India, and couples will often spend a substantial amount of their savings on their daughter’s dowry. Moreover, marriage in India is typically patrilocal. Upon marriage, women become part of their husband’s family and lineage and typically care for their husband’s parents in old age, leaving sonless couples with little support from their children in old age.

2. Declining Fertility – In recent decades, the number of children couples have in India has declined considerably. While women in India in 1970 had about 5.6 children on average, by 2018, women in India were on average having about 2.3 children over their lifetimes.1 Couples today also desire fewer children than they did only a few decades ago.2 The fact that couples are having fewer children means they have fewer opportunities to try for a son. Many couples seeking to attain their desired number of sons, while also limiting the total number of children they have, often resort to sex-selective abortion to achieve their desired family composition.

3. Unequal Status of Women – At its root, sex-selective abortion arises from discriminatory attitudes towards women and inequality between women and men in India. Women in India are often denied equal access to health care and education and are often excluded from decision-making in the family. Women in India suffer disproportionately higher mortality rates than would be expected for a country of similar socioeconomic development.3,4,5 Cultural biases often exclude women from inheritance rights and equal pay in employment. Women are often coerced or forced into selectively aborting their daughters by relatives or spouses.6 Studies have shown that men and women with gender equitable attitudes are significantly less likely to have a strong preference for sons.7,8

4. Accessibility of Ultrasound Technology and Abortion – Ultrasound is widely available and accessible across India and the cost of an ultrasound scan is affordable for most Indian citizens. In India, it is illegal to determine the sex of an unborn child. Prenatal sex determination is a lucrative business, however. Despite its illegality, the prenatal sex determination via ultrasound is still practiced in many parts of the country.

Abortion is also widely available and easily accessible in India. Abortion has been legal in India since 1974 when the Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act legalized abortion in most all cases up to 20 weeks gestation. According to one study, there were approximately 15.6 million abortions in India in 2015 alone.9

Click to View What Steps the Government of India Has Taken to Combat Daughter Elimination.

Prior to the widespread availability of ultrasound, couples in India sought to achieve their desired number of sons by having more children, practicing traditional methods believed to increase their chances of conceiving a son, or by practicing postnatal sex selection. With the availability of amniocentesis and ultrasound technology in India during the late 1970s and early 1980s, it became possible to easily determine the sex of an unborn child prior to birth.

In 1983, the Indian Parliament passed a law banning prenatal sex determination services at public hospitals and public health facilities. The law, however, did not apply to private health facilities and the practice of prenatal sex determination via ultrasound increased rapidly through private health providers.

In 1994, Parliament passed a law making it illegal for anyone—including health care workers at private institutions—to reveal the sex of an unborn child. The law was called the Pre-Natal Diagnostic Techniques (Regulation and Prevention of Misuse) Act (or “PNDT Act”). The PNDT Act went into effect in 1996. The PNDT Act required ultrasound clinics to register with the government and prohibited the advertisement of prenatal sex determination services. Health care workers that violated the law could be penalized with up to three years in prison and a 10,000 rupee fine on first offense and up to five years in prison and a 50,000 rupee fine on repeat offense.

The PNDT Act, however, was poorly enforced and the practice of sex-selective abortion continued unabated for several years after the law went into effect. In 2001, the Supreme Court of India in CEHAT v. Union of India found the Indian government responsible for failing to properly implement the PNDT Act and ordered the government to fully enforce the law.

In 2003, Parliament added several amendments to the PNDT Act and renamed it the Pre-Conception and Pre-Natal Diagnostic Techniques (Prohibition of Sex Selection) Act (or “PC-PNDT Act”). The PC-PNDT Act expanded the prohibition on sex selection to include preconceptional methods like IVF and sought to clamp down on unregulated mobile ultrasound clinics. The PC-PNDT Act also set up state-level supervisory boards to ensure that the law was being properly implemented and to create public awareness about the societal harms of sex selection. The new law also doubled the fines for persons seeking sex determination services.

A few years after the PC-PNDT went into effect, India’s sex ratio at birth declined slightly and has since leveled-off somewhat. In 2015, the government of India, in 100 select districts, launched Beti Bachao, Beti Padhao (Save the Girl, Educate the Girl) (BBBP), a national public awareness campaign to promote the birth, well-being, and education of girls. In 2018, the BBBP campaign was expanded to all of India. With the roll out of BBBP in 2015, the government also introduced Sukanya Samriddhi Yojana, a special savings program that allows parents of daughters to open savings accounts in their daughter’s name to save for post-secondary education. Sukanya Samriddhi Yojana accounts earn interest at a special interest rate tax exempt.

To the present day, however, the sex ratio at birth in India still remains highly skewed towards males. In 2018, it is estimated that the sex ratio at birth was nearly 111.

Click to View Solutions for Solving India's Sex-Selective Abortion Crisis

There are a number of steps the Government of India and other international stakeholders can take in combatting the practice of sex-selective abortion.

1. Effective Enforcement of Laws Banning Sex-Selective Abortion – In order to reduce the number of sex-selective abortions in India, the central, state, and union territory governments must ensure full and effective implementation of the PC-PNDT Act, including promptly holding medical practitioners that violate the law accountable. The government must ensure that all ultrasound clinics are registered, and that accurate, up-to-date records are kept. The Appropriate Authorities must also immediately investigate any clinics suspected of conducting illegal activity and must take swift action against clinics found to be in violation of the law. In districts where the law has been rigorously implemented, the practice of sex-selective abortion has declined sharply.10 Laws prohibiting the practice of dowry must also be rigorously enforced.

2. Promote the Equal Dignity and Status of Women – Studies have shown that men and women with gender equitable attitudes and husbands who display low relationship control are significantly less likely to express a strong preference for sons.11 Promoting the equal dignity and status of women will reduce son preference and thus reduce the motivation for couples to engage in sex selection practices.

3. Public Awareness Messaging to Combat Stigma Against Girls – Public and non-governmental stakeholders seeking to combat sex-selective abortion must promote the dignity of girls through public awareness messaging. Such messaging should not only reinforce cultural-based reasons why Indian couples desire daughters, but should also seek to advocate for the equal status of girls and their equal potential to contribute to their families. Public awareness messaging should also focus on segments of society most likely to practice sex-selective abortion. The Government of India should ensure that the national Beti Bachao, Beti Padhao campaign is fully implemented through all levels of government.

4. Promote the Rights of Girls to be Born and Discourage Recourse to Abortion – Public awareness messaging must advocate for the fundamental right of girls to be born. Combatting sex-selective abortion is fundamentally a human rights issue. Unborn girls have the inherent right to be born, and women have the fundamental right not to be coerced or forced into aborting their daughters. Harmful attitudes devaluing the life of the unborn must be done away with. The government should pursue life-affirming programs for women who feel they cannot raise another daughter such as offering options for adoption12 or conditional cash incentive programs or tax breaks to help offset the costs of raising a daughter.

5. Improve Socioeconomic Development – In the long term, improving socioeconomic development may reduce son preference, thus reducing the motivation for sex-selective abortion. However, socioeconomic development alone will not reduce the practice of sex selection in the short term. Studies have shown that demographic groups with greater wealth, income, education and urban residence in India are in fact more likely to selectively abort daughters than their counterparts.13,14,15,16,17

6. Conditional Cash Transfer Schemes and Other Incentives to Encourage Couples to Have Daughters – Conditional Cash Transfer (CCT) programs which provide couples financial incentives to raise daughters have shown moderate success in some places.18,19,20 CCT programs may be more likely to succeed if they are adequately funded, consistently sustained over a long period of time, are available to a large subset of the population, have high awareness among the target population, and provide payouts that amount to real money for program beneficiaries (i.e., they provide sufficient incentive for couples to participate). CCT programs have sometimes been criticized for providing tangible benefits for only low-income families as the payouts tend to be rather small. For middle class families, other incentives may perhaps be more beneficial such as tax breaks for parents of daughters and access to preferred interest rate loans for small business enterprise for qualifying daughters upon completion of schooling. Starting in 2015, the Government of India, through the Sukanya Samriddhi Yojana program, began offering parents of girls the option of opening special interest rate savings accounts to help save for their daughters’ education and to discourage early marriage.

7. Incorporate Involvement from Women’s Groups and Non-Governmental Organizations – Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and women’s groups have an important role to play in combatting prenatal sex selection, offering expertise and on-the-ground interventions within communities to effect lasting change in improving the socioeconomic status of women and can play an important role in discouraging recourse to abortion. Studies have shown that NGOs can have a real impact on reducing the practice of sex selection.21

8. End India’s Population Control Policies – The government of India has long promoted population control policies. These policies in turn help fuel the practice of prenatal sex selection. Six states in India currently have two-child policies that prohibit civil servants from having more than two children. Studies have shown that these two-child policies have caused a statistically significant male-biased distortion in the sex ratio at birth in states where they are in place.22 Some CCT programs promoting the birth of daughters also require one or both of the spouses to be sterilized. Such requirements are contrary to women’s rights as they incentivize permanent sterilization. They are also counterproductive as couples are not likely to apply to these programs until they have first attained their desired number of sons. In order for the Indian government to eliminate the practice of sex selection, it must abandon population control policies and incentives.

ENDNOTES

Click to View Endnotes

1 United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2017). World Population Prospects: The 2017 Revision.

2 International Institute for Population Sciences – IIPS/India, Macro International. India National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3) 2005-06. Volume 1, p.103. Table 4.16: Ideal number of children. Mumbai, India: IIPS and Macro International; 2007. Available at http://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FRIND3/FRIND3.pdf.

3 Sen A. Missing women. BMJ: British Medical Journal. 1992 Mar 7;304(6827):587.

4 Anderson S, Ray D. Missing women: age and disease. The Review of Economic Studies. 2010 Oct 1;77(4):1262-300.

5 Osters E. Proximate sources of population sex imbalance in India. Demography. 2009 May 1;46(2):325-39.

6 Puri S, Adams V, Ivey S, Nachtigall RD. “There is such a thing as too many daughters, but not too many sons”: a qualitative study of son preference and fetal sex selection among Indian immigrants in the United States. Social Science & Medicine. 2011 Apr;72(7):1169-76.

7 Priya N, Abhishek G, Ravi V, Aarushi K, Nizamuddin K, Dhanashri B, et al. Study on masculinity, intimate partner violence and son preference in India. New Delhi: International Center for Research on Women; 2014.

8 Robitaille MC, Chatterjee I. Sex-selective abortions and infant mortality in India: the role of parents’ stated son preference. 2014 Aug 18. Available at SSRN: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2557224.

9 Singh S, Shekhar C, Acharya R, Moore AM, Stillman M, Pradhan MR, Frost JJ, Sahoo H, Alagarajan M, Hussain R, Sundaram A. The incidence of abortion and unintended pregnancy in India, 2015. The Lancet Global Health. 2018 Jan 1;6(1):e111-20.

10 Guilmoto CZ. Sex imbalances at birth: current trends, consequences and policy implications. Bangkok: United Nations Population Fund-Asia and the Pacific Regional Office (UNFPA-APRO); 2012. pp. 22-23.

11 Priya (2014), supra note 1.

12 Srinivasan S, Bedi AS. Ensuring daughter survival in Tamil Nadu, India. Oxford Development Studies. 2011 Sep 1;39(3):253-83.

13 Jha P, Kesler MA, Kumar R, Ram F, Ram U, Aleksandrowicz L, et al. Trends in selective abortions of girls in India: analysis of nationally representative birth histories from 1990 to 2005 and census data from 1991 to 2011. The Lancet. 2011 Jun 4;377(9781):1921-8.

14 Sekher TV. Special financial incentive schemes for the girl child in India: a review of select schemes. Mumbai: United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA); 2010. p. 57.

15 Arnold F, Parasuraman S. The effect of ultrasound testing during pregnancy on pregnancy termination and the sex ratio at birth in India. In: XXVI International Population Conference. Marrakech (Morocco): International Union for the Scientific Study of Population; 2009 Sep (Vol. 27).

16 Bhat PM, Zavier AF. Factors influencing the use of prenatal diagnostic techniques and the sex ratio at birth in India. Economic and Political Weekly. 2007 Jun 16:2292-303.

17 Clark S. Son preference and sex composition of children: Evidence from India. Demography. 2000 Feb 1;37(1):95-108.

18 Brahme D, Kumar S. Financial incentives for girls—what works? New Delhi: United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA); 2015 Dec 16. Available at https://india.unfpa.org/en/publications/policy-brief-financial-incentive-girls.

19 Sinha N, Yoong J. Long-term financial incentives and investment in daughters: Evidence from conditional cash transfers in North India. The World Bank; 2009 Mar 12.

20 Lim SS, Dandona L, Hoisington JA, James SL, Hogan MC, Gakidou E. India’s Janani Suraksha Yojana, a conditional cash transfer programme to increase births in health facilities: an impact evaluation. The Lancet. 2010 Jun 5;375(9730):2009-23.

21 Srinivasan (2011), supra note 9.

22 Anukriti S, Chakravarty A. Political aspirations in India: evidence from fertility limits on local leaders. IZA Discussion Paper No. 9023. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2604386.