This Article is the first in a series of three which will examine the demographic crisis in Europe.

Europe is beautiful. The splendor of history meets us in every corner of this continent. History made by real people over the course of many centuries. Individuals who were able to make history because there was a generational renewal that wars and plagues could not stop. But now, without wars or plagues, generating future Europeans is one of the big challenges of the Old Continent. Demographics are not playing fair to Europe. It would be sad to say that Europe has more history than future, but right now it looks that way.

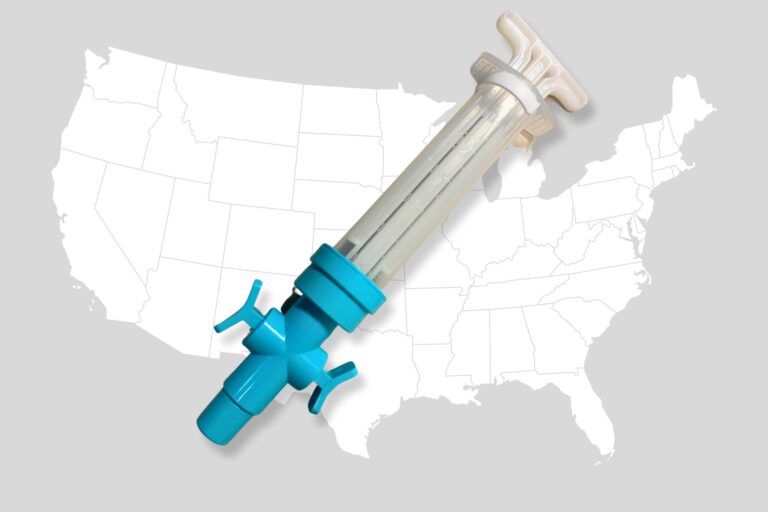

“Blue Cards” to Do What Europeans Aren’t Doing

At present, there is a debate in Europe about the creation of a card granting special permission to work for qualified immigrants (it is called a “blue card,” reminiscent of the American “green card”). The origins of this debate are the increased number of non-qualified immigrants and the demographic crisis which is now evident.

Europe is facing a demographic crisis. Forecasts show that by 2050 two workers will have to support one retired person, compared with four workers now. Could immigration be the answer? One suggestion is a “European blue card system” for skilled Third World workers.

European Commission vice-president Franco Frattini says the EU must learn to compete with the U.S., which attracts most of the mobile skilled labor in the world. He therefore proposed the “blue card,” a specialized residence permit for skilled Third World workers, which would ensure equal treatment at work. It would allow them to live and work in a given EU member-state for an initial, renewable, period of two years, after which they could work in another EU country. “We have to look at immigration as enrichment and as an inescapable phenomenon of today’s world not as a threat.”1

Here in Europe, with a fertility rate of only 1.5 children per woman, the notion of a “demographic winter” is as common as “pollution” is for a citizen of Mexico City or “hurricanes” for Caribbean or Central American people. And suggestions for how to face this demographic winter are almost as unproductive as actions taken for pollution or hurricanes in those places.

Population Statistics

In a recent report entitled Evolution of the Family in Europe 2007, the Institute for Family Policies, published these statistics:

-

75 percent of population growth in 2006 was the result of immigration and not of natural increase.

-

80 percent of population growth between 1994 and 2006 was the result of immigration. Of the increase by 19 million in the EU27 [the 27 member-states presently comprising the European Union] between 1994 and 2006, almost 15 million was the result of immigration (79 percent). This disproportion has increased over recent years. Between 2000 and 2006, 83 percent of population growth (10.9 million) was the result of immigration.

-

EU immigration is now 50 percent greater than the figures for the U.S.

-

Natural increase has remained static over recent years (around only 310,000 persons/year), which is significantly lower than U.S. figures.

-

Natural increase in the U.S. (percentage of the population) is 12 times greater than in the EU.2

Immigration has become the basis of population growth in almost all European countries. For example, rates of immigration in Spain are 10 times higher than the country’s natural increase rate.

Some Aspects of an Incomplete Analysis

In March 2000, an Extraordinary European Council took place in Lisbon. It focused on technological and labor challenges in times of knowledge and innovation. Demographics was included as a topic but it was not the primary focus.

In monitoring reports European councils have recognized six factors that prevent full-time employment. The sixth factor is: “European demographic trends, in particular an ageing population.”

Other European councils since Lisbon have focused on demographics. “The European Councils at Stockholm (2001) then Barcelona (2002) emphasized the size of the demographic challenge in the EU. The reforms presented by the EU are part of the renewed Lisbon strategy and respond to a common perspective of restored confidence.”3

In 2005 they moved a step ahead in that direction. “[The] Commission has published a Green Paper on demographic change and highlighted the challenges the European Union has to confront: falling populations, continuing low birthrates and continuing increases in longevity.”4 Of course, the worry and concern are increasing.

Green Paper: The Same Story

The Green Paper mentions three reasons to explain this multi-aspect problem. “Analyzing the full-time employment and social and retirement pension balance:

-

continuing increases in longevity as a result of considerable progress made in health care and quality of life in Europe;

-

the continuing growth in the number of workers over 60, which will stop only around 2030, when the baby-boomer generation will become ‘elderly;’

-

continuing low birthrates, due to many factors, notably difficulties in finding a job, the lack and cost of housing, the older age of parents at the birth of their first child, different study, working life and family life choices.”

The Real Problem

Well, in truth, the only real “problem” with these points is the third. But unhappily politics are not clear enough to give a real solution. Actually politicians don’t want to touch the essence of the matter: they have created a culture that does not welcome babies and to reverse it you need more than macro policies.

Some lines ahead, the document adopts a kind of dramatism:

The EU must accept that young people are becoming a rare resource and are encountering difficulties in integrating in economic life, notably the unemployment rate, the “risk of poverty” (i.e. a net income less than 60 percent of the average) or discrimination on the grounds of their age and lack of occupational experience…. In this context, a low birthrate is a challenge for the public authorities.

A challenge that, obviously, is still unsolved in this continent.

The report makes this interesting point:

With life expectancy increasing all the time, there are an ever-rising number of very elderly persons. Families alone will not care for those people and appropriate care will be needed; today this care is provided by families and particularly by women. Families must therefore be supported to a greater extent. This is where social services and networks of solidarity and care within local communities come in.

A Lack of Balance

Why couldn’t families by themselves take care of the old people? Since they have always done it, why would they now be unable to do so? The answer is because they foresee that traditional families are on the decline.

There is no balance between the increasing number of old people and the families that, in normal conditions, take care of them. Pensions are really the smallest problem because they can be “easily” solved with money — saved, well distributed or whatever. The problem is the human factor in all of this. How much could it cost the warm hand of a granddaughter holding her grandfather’s hand walking in any of the wonderful parks that all European governments maintain so splendidly?

Government Dilemma

Is it not sad to see governments attempting to help families do something it is supposed they can’t do by themselves and the only outcome is a big package of taxes, making people not wish to get married and raise a family?

It seems that is what is happening in Europe: They charge a lot of taxes to the families to give them some protection plans. The problem is that the taxes are paid first and the plans come later, or too late, and usually are very small. In the meantime, the analysis of the European Council only mentions the “reasons” (excuses) for the scarcity of families. It doesn’t make any attempt to enable families to care for their own elderly.

The debate about the “blue card” made by the press office of European Parliament contains a clever question that makes the point: Will the European “blue card” solve problem of aging population? It is evident that the answer is no. It is necessary to change the paradigm and radically alter the way they view life. The only question now is: Will Europe discover this in time?

Endnotes

1 http://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/public/story_pages/018-10568-267-09-39-902-20070921STO105548-2007-24-09-2007/default_en.htm.

2 http://www.ipfe.org/Report_Evolution_Family_europe_2007_EU27.pdf.

3 http://europea.eu/scadplus/leg/en/cha/c10160.htm.

4 http://europa.eu/scadplus/leg/en/cha/c10128.htm.